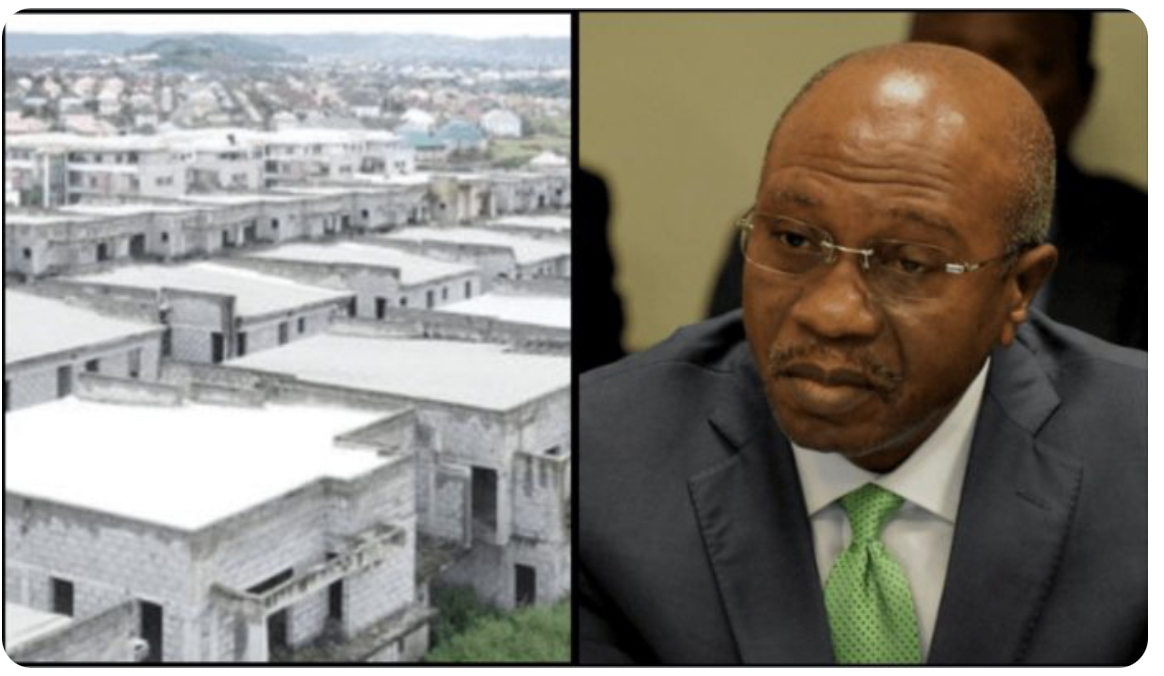

Former Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), Godwin Emefiele, has formally petitioned the Court of Appeal in Abuja to overturn the controversial forfeiture of a massive estate in Lokogoma, Abuja, comprising 753 housing units, which was ordered to be forfeited to the Federal Government in December 2024.

The forfeiture, obtained through an ex parte motion by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), has been touted as the agency’s largest single asset recovery in history. However, what lies beneath this seeming success is a troubling tale of concealment, procedural irregularities, and apparent disregard for due process — a tale that now threatens the credibility of the EFCC’s anti-corruption mandate.

Emefiele cries foul

In an appeal filed on April 30, 2025, through his counsel A.M. Kotoye (SAN), Emefiele argued that the forfeiture was obtained through misrepresentation and material concealment of facts. He accused the EFCC of failing to properly notify him of the proceedings, despite ongoing legal engagements in other criminal matters, and of publishing the interim forfeiture notice in an obscure section of a newspaper, effectively denying him the constitutional right to respond.

“The EFCC deliberately kept me in the dark,” Emefiele alleged, noting that at the time the forfeiture was filed and granted, he was already defending himself in three criminal cases across Abuja and Lagos.

The appeal is anchored on four legal grounds, including misinterpretation of Emefiele’s application by the trial judge, who treated it as a response to an interim forfeiture rather than a proper motion to set aside a final order; breach of natural justice, as Emefiele claims he was not served and was denied a chance to be heard; absence of jurisdiction, arguing that the proceedings were procedurally flawed; and lack of credible evidence, stating that the court relied on hearsay, suspicion, and unsubstantiated claims.

Emefiele insisted that he holds both legal and equitable interests in the estate, which was originally linked to another unnamed government official before his name was drawn into the matter.

Despite a pending appeal at the Court of Appeal, the Federal Government recently announced its intention to sell off the estate, a move that legal experts have warned could violate the principle of lis pendens, a legal doctrine that forbids dealing with a property that is the subject of ongoing litigation.

“This is not just a legal misstep; it is an act of executive lawlessness,” said a constitutional lawyer. “A notice of appeal has been filed and served, yet the government is moving to dispose of the property. This is not how justice works.”

If the Court of Appeal eventually sets aside the forfeiture, as it previously did in a similar case in Lagos, where the EFCC also lost, it would mean that the government has unlawfully sold a private citizen’s property, creating not only a legal crisis but also a moral one.

Observers have noted that the EFCC’s sudden filing of fresh charges against Emefiele, while the appeal on the forfeiture is ongoing, could be seen as a tactic to distract or overwhelm him legally. Already burdened with multiple cases in Lagos and Abuja, Emefiele is being ferried from one court to another, raising concerns of judicial harassment and prosecutorial misconduct.

Is the EFCC grasping at straws to defend a flawed process? Or are we witnessing a dangerous weaponisation of the judiciary under the guise of anti-corruption?

In the interest of justice, the EFCC must submit to judicial oversight and refrain from extrajudicial manoeuvres. The Federal Government, on its part, should suspend all plans to sell the estate until the Court of Appeal rules on the matter.

To proceed otherwise would not only violate legal precedent but also erode public trust in the country’s anti-corruption framework. The EFCC’s reputation hinges not just on high-profile arrests, but on its adherence to due process, transparency, and legal integrity.

If the courts are to remain the last hope of the common man, they must not become tools in the hands of overzealous prosecutors. And if the EFCC’s fight against corruption is to be taken seriously, it must be grounded not in theatrics, but in justice.

Credit:Guardian